words by: simon freeman & liam mcintyre

photos courtesy of: liam mcintyre

generously provided by: like the wind magazine

More than once during recent history, football’s loss has been running’s gain.

Sir Mo Farah was so obsessed with football as a young boy growing up in north London that his school sports teacher would bribe him to train or race on the track with the promise of some extra time kicking a ball.

Growing up in Jamaica, Usain Bolt was also a huge fan of football (although cricket was his first love, but let’s not allow that to get in the way of a good tale). Bolt even tried to forge a career as a professional football player after he retired from sprinting.

And Norwegian trail runner Yngvild Kaspersen talks about the fact that as a youngster, her focus was all on playing football before running in the mountains ever entered the scene.

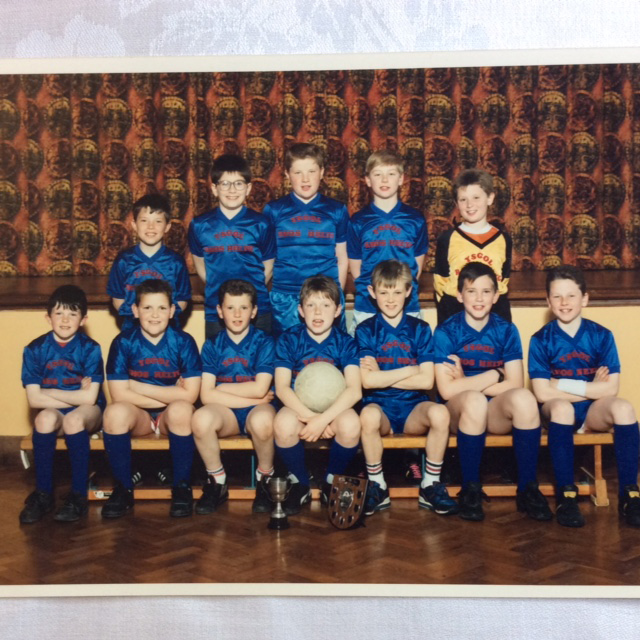

I discovered not so long ago that a runner with whom I’ve trained for a few years might also have enjoyed a career as a professional footballer. Growing up in north Wales, football occupied the central part of Liam McIntyre’s life. It is perhaps the quality (or should that be curse) of becoming obsessed with something that has taken Liam to the heights he has achieved in football, music and – of course – running. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Liam was born in Halkyn, Flintshire, to an Irish father and Welsh mother. He is one of four boys. A quick search online reveals that Halkyn seems to be pretty unremarkable. Aside from being the birthplace of Dan Jones, who translated The Book of Mormon into Welsh, there doesn’t seem to be much else about the place worth mentioning. Except if you talk to locals. They will tell you that Halkyn is in fact a bit of a beauty spot. In particular Halkyn Mountain attracts droves of walkers and ramblers who visit for the beautiful views.

Importantly for this story, just beyond the village boundaries existed something of a hotbed of football talent. Fourteen miles away is St Asaph, birthplace of Ian Rush, former Welsh international and leading goal-scorer for Liverpool.

Nine miles from Halkyn lies the village of Mancot, where both Gary Speed (former Welsh player and team manager) and Kevin Ratcliffe (who appeared 359 times for Everton) were born. And 15 miles east, just across the border into England, is Chester, birthplace of English ace Michael Owen.

“Michael and I met when we were about nine years old,” Liam tells me. “We played on the same teams and against one another. So he is definitely a contemporary of mine.”

In his book Bounce, former international table-tennis player turned journalist Matthew Syed wrote about the importance of easy access to facilities and inspiration. In his case, there was a group of children interested in ping pong, a teacher who wanted to encourage their passion for the sport and a facility where they could play 24/7. For Liam, the ingredients were two older brothers who were both dedicated and talented footballers (Liam’s younger brother went on to be a top-class rugby player – it often happens like that), local legends like Rush and Ratcliffe, and contemporaries such as Owen.

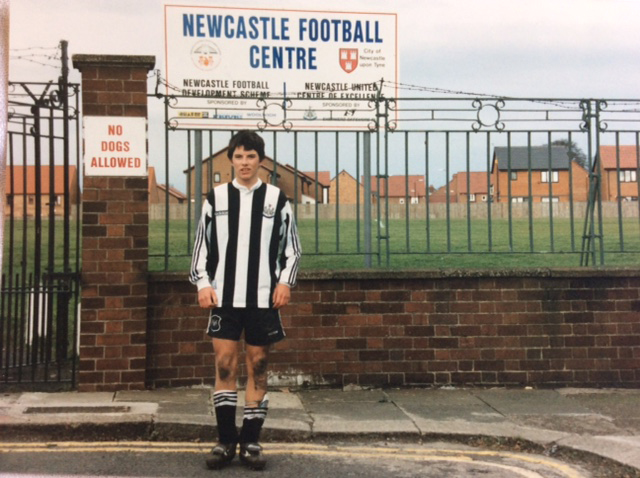

Liam earned the opportunity to play for Newcastle United’s youth team: the first step towards a professional career. His eyes light up when he talks about the experience of training with first team players such as Peter Beardsley, Faustino Asprilla and David Ginola.

But Liam’s tilt at a football career ended when – aged only 17 – he was released by Newcastle. Even now, decades later, it is clear that this experience hurt him deeply. In fact, an aspect of that – being judged by others – is perhaps one of the driving factors in Liam’s love of running.

Following his departure from the Newcastle squad, Liam was offered contracts with other teams. But he says he felt burned out and worried about the future. So he returned home to north Wales to take some high school qualifications.

“I still played a bit of football then. I played for Holywell Town in the Welsh League. I was only 17 or 18 years old and playing against adults,” explains Liam. “But I was also pursuing my interest in music and doing my A-Level exams. Perhaps that was part of the problem at Newcastle: I was not 100% dedicated to the game. I always had music, for example. Some of the other players thought it was odd that I played guitar and piano.

“I guess at the time I left Newcastle I regretted not being as committed as the others. Then of course Michael Owen burst on to the scene. It wasn’t an easy time for me.”

The sense of loss is palpable. And seems to be fuel for what would come next.

Liam went to university in Cardiff. It was a very sporty university so he continued to play football while completing a science degree. And it was at university that Liam started down the road towards his second career, this time in music – a career move that would end up being another example of how other people’s opinions can override talent or hard work.

Rock’n’roll is famous for excess and pushing the limits. The cliché is that very few rock musicians look after their health (hats off to Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers for bucking that trend, by the way). In his mid-20s Liam moved to London with his band and threw himself into long days at work and evenings and weekends rehearsing or playing gigs.

“I really wasn’t living a healthy lifestyle,” he remembers. “And eventually it caused problems. By the time I was in my late 20s I was struggling with anxiety and depression – although I hardly realised it at the time – and that resulted in me leaving the band. I moved out of London. I look back now and see that in my 20s I was really bouncing off the walls.”

By 2010 Liam had started working as a musical director of touring stage shows. He’d met his wife, Jen, and moved back to London. But the habits he’d picked up during the years with the band were hard to shake off.

“After Jen and I got married, I decided to get a proper job. We wanted our own place and for that I needed a bit of financial stability. But all the time the anxiety and depression were creeping up on me. I was drinking a lot more than I should have been and smoking. I lost all my confidence. I was having these horrible panic attacks.”

Liam describes how some days it would take a superhuman effort simply to get on the tube to go to work. And all the while this was going on, exercise went AWOL.

Liam says that his wife was a huge support through those dark times. But he also acknowledges that he refused to tell anyone else about what was afflicting him. Even his brothers and parents were unaware of how bad things had got.

“Then, suddenly, there was a chink of light,” he says. “It started with telling my family how bad I was. That started my recovery. But it was slow.

“Then, completely coincidentally, in 2016 a school friend, Mark Parry, contacted me to say that he was running the London Marathon for a Welsh cancer charity. He wanted to come and stay at our place in London for the race.

“After three years of really serious depression, just being around my friend and seeing him run the marathon sparked something in me. I could suddenly see a way forward.”

The following year Liam’s friend chose not run the marathon again. Instead, he put Liam in touch with the charity. Liam began to raise the required £2,500 and started training.

“I really didn’t know what I was doing. I’d read that I had to do a long run, so I’d leave my house and run to a friend’s place. We’d go to the pub for a pint and I’d run home. The rest of the time, I trained like a footballer – just going out and sprinting as hard as I could.”

It was around this time that Liam and I met.

My running was on a downward slide. From being someone who used to run nine times a week, regularly clocking 100 miles in training, I suddenly had my hands full launching two businesses. In a selfish attempt to create reasons to pull on my trainers, I organised a group run every Wednesday morning from my office to a local woodland and back.

Liam’s wife found out about the group and came into the office to sign her husband up. I was delighted to have a new running companion. Little did I know what would follow.

Six months after Liam started running with our group, he finished the London Marathon in 5h36m. His family saw him with a mile before the finish and thought he was about to collapse, that’s how bad he looked.

But Liam reports that the elation of finishing was huge. And there was something else. Unlike with football or music, Liam had found an activity where he was largely in control of the outcome. There were no football coaches making decisions about who to keep and who to release. There were no music critics deciding which bands would make it and which wouldn’t.

“I realised that with running, to a large extent your time at the end of the race is up to you.” Explains Liam.

Some seeds, once planted, take root and begin to grow in a slow and steady fashion. Others explode into life. And so it was with Liam’s love of running. Liam went all in.

Immediately following the London Marathon, Liam felt himself slipping back into anxiety and depression. So Jen signed him up to some races. At a 10km race a couple of months after the marathon, Liam clocked a finishing time of 49 minutes. Around the same time he quit drinking and smoking.

Like many runners who really get into the sport, Liam knows he did too much too soon. An injury during the second half of 2017 forced a temporary pause. Liam took to the bike and set his sights on the Rock’n’Roll Liverpool Marathon in April the following year.

Having told his long-suffering family that his aim was to merely lop two hours off his previous time, they were all sat in a café and missed him as Liam cruised to the finish line in 3h10m, setting a personal best by a rather improbable two-and-a-half hours.

Having achieved what he had with a combination of the Strava app on his phone (no smartwatch at that point) and a downloaded McMillan training plan, Liam added run-commuting to the mix – six miles to work each morning and the same back each evening – and continued to research and learn about training, kit and nutrition.

Liam’s progression was a source of pride and wonder to those of us who ran with him every Wednesday morning. Late in 2018 at the Chester Marathon, Liam clocked his first sub-3 hour finish.

Then in April 2019, Liam ran the Manchester Marathon in 2h46m30s.

And in September that year, in Berlin, Liam finished in 2h32m47s.

“I really didn’t know I had this drive in me,” says Liam “The willpower to train as much as I do comes from the buzz I get from racing. I really enjoy learning all the time. And I like being self-reliant – working out my own training. Of course, running has gone from being a hobby to a lifestyle now.

“I really know that I am a better person to be around when I am running. And when I have a target. The routine and the rhythm is crucial to me. Covid-19 has been really disruptive in so many ways. But I have stuck to my training and in fact I have been running more than ever since I have been working from home.”

Of course, the cancellation of so many races has been a source of frustration.

“At the start of the year I ran the Big Half in 70 minutes. I definitely thought that meant I had a shot at a sub-2h30m marathon in London this year. But that race was postponed from April to September and then cancelled altogether. So my next target is that I have unfinished business in London. I want to run the Championship race and see whether I can get that sub-2h30m finish. Then I don’t know. Now I’m 40, I like the idea of trying to get a Masters’ team place. It could be on the English or Welsh Masters’ teams. Although I’m not sure my family would forgive me if I ran in an English vest …”

This journal exists in part to understand why we run. For Liam, there are so many reasons. And clearly they all contribute to how he sees and values himself. So what would happen if for some reason he couldn’t run?

“I do worry about not being able to run for whatever reason. When I run, I face everything in my life – work, the law degree I’m studying for, family – with the same energy. Without running, I know I can start to feel anxious again. I start to slip back. And I don’t know what I would fill the gap with. It’s a worry.”

Thankfully for now, it seems that there is no stopping Liam McIntyre. A wet and windy lockdown-style marathon that didn’t go to plan a few months ago was embraced as a learning experience. There is even talk of starting to work with a coach. Whatever the future holds, Liam is a great example of how dedication, patience and passion can achieve so much. And there is a football coach in Newcastle who probably missed out on a great player. But then again, as I wrote at the top of this piece, football’s loss is running’s gain.