Words by: Jeanne Mack

Illustrations by: Sarah Cotton

A week had passed, and I still couldn’t go down stairs. Shuffling my feet as I creaked into an about-face at the top of a staircase to descend backwards made it a bit easier. But not much. Any bodily motion I made left me feeling like a colony of tiny, irate gremlins had settled into my lower body in order to work their anger out by using my muscles as punching bags.

It’s a little funny that some of the theoretically-best things you can do for your health are bound to leave your body feeling worse for much longer than some of the worst things you can put your corporeal form through. Drink a gallon of whiskey and eat three tubes of raw cookie dough and sure you’ll be hungover with a stomach ache—and a sprinkling of salmonella—but within a day or two, you’ll probably be fine. Able to get through your day pretty normally. Your kidneys and pancreas are a little worse for wear, but that won’t be noticeable for years. Conversely, go for a run that turns mostly into a hike down and back out of the Grand Canyon, and you’ll be barely able to walk for around ten days, at least in my experience.

I’d never seen the river. In the two years that I’d been living an hour and a half drive away from the Grand Canyon, I’d only visited it three times. But each time, we’d hiked down for a while without any real intention of making it to the bottom, then turned around after a few hours to get back to the top before dark.

I knew I was moving away from Arizona in about a month when I texted my friend Stephen, “I want to run in the Grand Canyon before I leave.” I wanted to make it to the bottom of the canyon, I wanted to watch the water of the Colorado River stream by me, on its way southwest to the Arizona-Nevada border.

I’d barely been running consistently when I decided I wanted to go. A stress injury in my left foot had sidelined me for the spring, so I didn’t have much of a base to work off of. Which meant running down the Grand Canyon and then back up it would not be easy. Still, this run felt like the best way to say goodbye to the place where I’d learned to love running again.

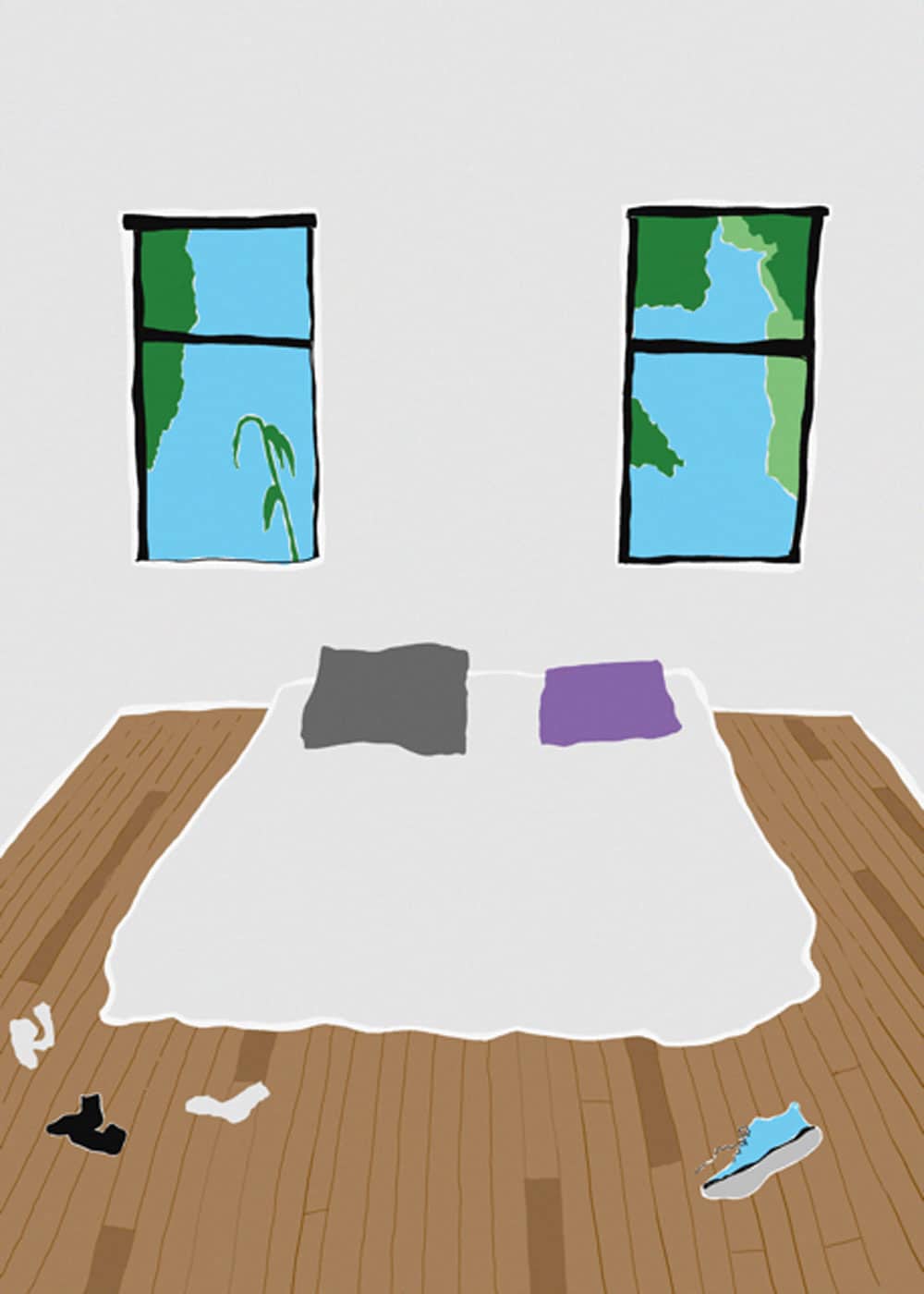

The days leading up to driving to the South Rim with Stephen and Maddie were filled with moving logistics for me. I operated at my most frenetic frequency—selling off furniture, boxing up books, and shoving sweaters into trash bags. I sprung off of my floor-mattress (after I’d sold the bed frame) at the sign of first light in the morning and began putzing, dusting, vacuuming. The night before we were going to the canyon, I sorted socks into piles of: “keep”, “maybe keep”, “have only one hole that I could possibly fix if I learned how to darn”, “upwards of three holes”, “shredded fabric”, then set my alarm for 5:00 AM and stared at the ceiling for a while before falling asleep. Thinking of what still needed to be done before I left Arizona.

Maddie and Stephen met at my house a little after 5:30 and I loaded dry clothes, water, and snacks into Stephen’s trunk. I’ve found that snacks are right up there with views as my favorite part of long trail running.

The ride from Flagstaff to the Canyon is at times both beautiful and boring. We stared through the windshield at the burnt-out stands of blackened, limbless trees on mountains. It had been an especially dry winter and spring in the area. The land had an underlying tint of thirst, and muted yellow. Fire danger was so high in Flagstaff as we drove away that the trail system was scheduled to close to the public the next day. As the mountains settled into our rearview, we counted cows in the tall, brittle grass at our sides.

I was nervous about getting completely dropped by two talented trail runners who’d made trips down and out of the canyon before. With their prior experience, Stephen and Maddie both had a clear picture of what they were getting into. I was blindly following their lead.

We spooked a pair of elk back into the woods when we turned into the parking lot and hopped out to layer sunscreen on our necks and ears and shoulders. We shared some pre-run snacks in the shade of the car and loaded water into my vest, Maddie’s handheld bottles, and Stephen’s belt. Stephen spent a good ten, maybe fifteen, minutes trying to figure out how to tighten and fasten the belt, and then we set off.

We jogged pretty slowly across the parking lot to make it to the South Kaibab trailhead. Stephen insisted that going down South Kaibab and then along the river and then back up Bright Angel was our best bet in terms of routes. South Kaibab is shorter, but steeper, and has nowhere to re-up on water along the way. It’s better to do that trail first, not second. I nodded mutely to whatever he and Maddie recommended, very much along for the ride.

We were at the trailhead around 7:00 AM and collectively glared at a residual sign that warned us about “Icy Trail; Crampons Recommended”, since it was already about 75 degrees and very sunny at the top. It was only bound to get hotter, especially at the bottom. Then, we hit it.

We went fast. Much faster than I would have anticipated being able to go on the steepest, sandiest downhills I’ve ever encountered. I use the plural form, because it truly felt like a fresh descent every hairpin turn I made. Maddie and Stephen were ahead of me, somehow fearlessly flinging their bodies forward at full speed. I was extremely conscious about just how far there would be to fall if I slipped, or tripped off the side, in a way I’ve never noticed in myself before. They were mountain goats, hopping and leaning forward and further forward as I struggled and hurried to pick my steps.

I was grateful for each mule train that passed, which meant we had to stop and stand off to the side as the line of mules climbed up the trail. It gave me moments to catch up to my friends and grab water.

“Drink before you’re thirsty,” Maddie had warned before we started.

There were places to refill bottles at the river, and if your pack wasn’t almost empty by the time you got there, you were probably doing something wrong.

The stops for mules also afforded me the chance to look around—to lift my eyes from their laser focus on footing into the sky. Sky was everywhere, spilling outward into more space than usually possible. The river was just a speck in the distance, still so far away and my legs were already a little shaky. I knew I’d make it, I just wondered how much longer.

The Great Unconformity was first observed by John Wesley Powell—a soldier and geologist—in 1869. I learned about it from a friend in one of my graduate school classes just this past year. It’s a portion of rock that should be represented in the layers of sediment that make up the Grand Canyon, but yet is nowhere to be found. The missing section represents time that has somehow vanished. To oversimplify: strata of very different geologic matter from distant eras press right up against each other, without the linking chunk that should come between. In some places, it is as many as 725 million years that are not expressed at all in the rock record. That is a lot of lost time.

Hearing about it this fall made me even more interested in the canyon. It added a layer of mystery underneath the overarching beauty of the natural monument. It made me want to spend more time there, get to know the place better.

I reminded myself of that desire as the last mule rider passed us, asking us if we knew “a Jim”—meaning renowned Flagstaff trail runner, Jim Walmsley. We started downward again, we were over halfway to the bottom. My calves were already feeling it. I let Maddie and Stephen go, and tried to find a rhythm, tried to loosen my grip on the fear of falling. I’d catch myself. Probably.

Then, we got close enough to the bottom for the trail to even out and for me to breathe regularly and glimpse a bright blue green sliver of water. A few bridges spanned the width of it every mile or so, it seemed like. I hadn’t expected the bridges and I loved them. They were beautiful, sitting on cables that were seemingly strung out of rock walls. Each and every one. We ran right over the top of the water. I looked down at it swirling directly below my feet. Then we kept going.

We ran together along the sandy beach-surface right by the river. We stopped for gels and blocks and jelly beans and more water. I’d done a pretty good job of forcing myself to drink on the way down. Read: I’d survived. We’d made it there in under an hour, faster than I’d expected for sure. I was ready for the change of direction.

We didn’t spend a ton of time by the river. The thought of having to get back up hung over us, more than a little daunting.

On the way up, Maddie stayed with me as I tried to piece together spurts of running. It was humbling, to say the least. Realistically, most of the time we power-hiked. As a hike, it was an A+ performance. As a run, not so much. We had more time to look around. To take in the reds and browns of the rock surrounding us. The reasoning behind the unconformity’s existence is mostly: erosion. The material that once existed there was eroded down to nothing at some point before the next layer of rock appeared. It’s hard to imagine that millions of years spent building up sediment and rock was able to be so completely undone.

On the way up, Maddie stayed with me as I tried to piece together spurts of running. It was humbling, to say the least. Realistically, most of the time we power-hiked. As a hike, it was an A+ performance. As a run, not so much. We had more time to look around. To take in the reds and browns of the rock surrounding us. The reasoning behind the unconformity’s existence is mostly: erosion. The material that once existed there was eroded down to nothing at some point before the next layer of rock appeared. It’s hard to imagine that millions of years spent building up sediment and rock was able to be so completely undone.

Unsurprisingly, we made it to the top in much more time than it took to get to the bottom. It was starting to get very crowded with other canyon visitors the last hour or so of hike-running, and Maddie and I were both ready to be done. We stopped for the bathroom and water a couple of times then motored on as fast as we could. We inched closer to the top of the rim. It jutted out above us, teasing me into thinking it was just a few minutes away as we switch backed our way up. I wanted to run at the top, I envisioned gutting through the last half mile, in some symbolic show of finishing strong. But really, it was kind of too crowded to do that anyway. I was a bit relieved.

At the top, it felt good. I was tired—maybe depleted is a better word, but happy. It was over. Done. We cleansed our sweat with baby wipes, erasing the trail of salt down the sides of our cheeks and chins. I couldn’t imagine putting one more chemically-engineered glucose carbohydrate mixture into my body and we were pretty much all on the same page about that. We made our way to the general store further inside the park and picked up some potato chips and ice cream. You know, real food. It was amazingly delicious.

When Stephen dropped me off at my house a couple hours later, my roommate had cleared out all of his things. The house was practically, entirely empty.

My legs were already starting to feel sore. I was too drained to be emotional about the bare walls and floorboards as I collapsed onto my floor mattress and tried to sleep.

The next day, I finalized emptying the house and cleaning everything and the day after that, on my flight away from Arizona, I was still just as exhausted. I was sad to leave, but I’d packed too much activity into my last few days to feel much of anything. The memory of the canyon reached through my fatigue, though. The trip to the river and back inserted itself into my body with sharp, twisting pinches up and down my IT Bands that I felt with any movement. I waited, wondering when the soreness would fade and erode away, to be replaced with stronger muscle fiber. And whether I really wanted it to.